Written by: Leah F. Cassorla, Visiting Assistant Professor of Writing and Rhetoric at the Allan K Smith Center for Writing and Rhetoric, Trinity College, Hartford, CT.

Perhaps my favorite meme in the last few months has been a bag of Frito Lay’s chips with the flavor combination for 2020: Orange juice and toothpaste.

Here, in classic internet form, is a swift and meaningful commentary on the horribleness, predictability, and yet surprising nature of the year so far. Other memes capturing this year have included 2020 bingo, and “wagers” on what each new month might bring.

It seems senseless in the face of such a year to call it good or bad. It seems silly to call it anything or to believe I would know how it would feel to be other than who and how I am in this year of nothing-like-anything-I’ve-ever-experienced. And yet, I’m tempted to say it’s been a good and bad year to be contingent faculty at a small liberal arts college on the East Coast. I’m tempted to say there’s a great deal more good - and that the good has come from the bad.

I was fairly taken aback when I came to my new SLAC (Selective Liberal Arts College) and found that the same campus that had hired me, a specialist in computers and writing and how the digital world has changed the world, was a place where most professors banned the use of electronics in class; all electronics, even for note-taking, except by accommodation. The surprise was compounded when I realized that my own style of teaching, which understandably depends heavily on computers, seemed not just odd to the people who had hired me, it seemed to some completely removed from the teaching of writing.

Don’t misunderstand, please. I am aware of the rampant Ludditism in academe. I am saddened by it, but I’m not completely naïve. What I was astonished by was the complete lack of recognition or acceptance of what I took to be some basic facts about higher education and technology

And then, well, the novel Coronavirus became part of our lives.

We headed out to Spring Break knowing we would not be back for the academic year and talking about moving online. I watched the dour expectations arrive on screen as my colleagues used the faculty list-serv; some to denounce the technology most of them banned from their classrooms and were now forced to build their teaching around; some to laud it; some to share their fears, but also their hopes; and all to struggle through what it meant for them as scholars and professors.

And though I had taught my first online class in 2004, I found the shared struggles and worries productive for my own students’ concerns and needs, as well as for my teaching . I also found that my students, all “digital natives,” forced me to reimagine my own understanding and expectations for online work and what it means to be a digital native.

I’d like to step back into the naïve world, first, in which a project that included 3-D printing was radical, and consider myself, my colleagues, and my students, as well as the transformation in our lives over the past half year. I’d like to do so in part to help myself to process it. But also because I think that we have, as Charles Eisenstein points out in his essay The Coronation, an opportunity with the novel Coronavirus—and I’d like to explore that opportunity here.

As I mentioned. My first response to my SLAC at the new faculty orientation when I found out that the majority of professors on campus did not allow the use of laptops, or any other electronic device, in the classroom, was surprise. The conversation at orientation centered on note-taking. Professors understandably argued for neuroscience studies that have shown that longhand writing of notes has better outcomes for memory and retention as well as for transfer in most students. I am not one to argue with science. But, being only human, I thought back to my own experiences in my second year of graduate school, when inflammatory arthritis had begun setting into my hands and three-hour courses made longhand note-taking no longer an option for me. It was blessed relief that my professors allowed my laptop in class, even before my diagnosis. Still, I kept myself open to the debate.

The next point of contention was even more crucial to my growing understanding of “the other side” of the technology debate. Some professors on my campus did not allow note-taking at all. “We are in a conversation; I want all my students to be fully present in that conversation.” I was taken aback. Immediately, I began to question the value of note-taking in a composition class. I realized that the majority of the note-taking was done only on certain days—when we covered technical issues like online research or citation, or particularly tricky grammar issues the class seemed to struggle with—and that the rest of the time, we really were mostly in conversation. Suddenly, resistance started to become my friend.

When I began teaching that fall, things went fine in my laptop-mandatory classes. Students sometimes forgot to bring their laptops, and we held classes in which their laptops weren’t necessary. I felt somewhat freed by the idea that note-taking was not necessary. I even came to embrace the realization that note-taking is not necessarily a sign of anything. As a writing professor with ADHD and dyslexia, however, I did encourage my students who needed or wanted to doodle or fidget with whatever they chose to, as long as the rest of the class was not affected by it (this is a standard I have always encouraged).

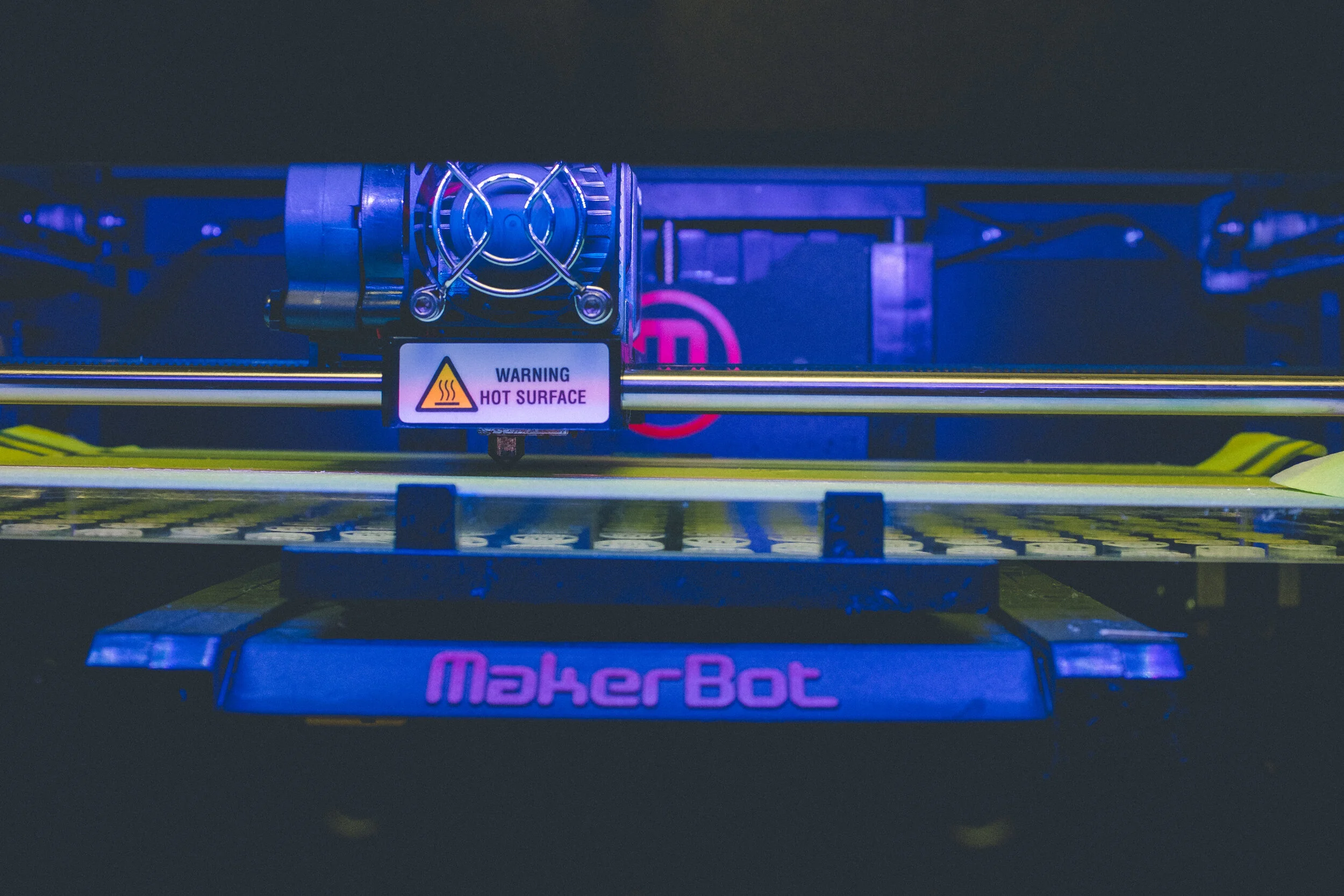

Toward the end of the semester, in a program staff meeting, we were discussing approaches to essay writing and I explained that I assigned my students a major project for the semester which used 3-D printing in tandem with essay writing to help students literally feel what process is about. I had found that this project was welcomed by the students, even though it was demanding and took up much of our semester. Many were excited to learn about 3-D printing, and there was the added benefit of its exotic-ness for sure, still in their reflections, students truly seemed to grasp how the reiterative nature of the editing process for 3-D printing and for writing were similar, and how reiterative, revision-based, process approaches to their work was beneficial. Many said it was their favorite project.

My colleagues, however, seemed less enthusiastic. It came off as a gimmick This came as a blow. I thought I wasn’t making the course about 3-D printing; I was using 3-D printing to make the course about process. It took me time, but I realized this was an opportunity to make the project more clearly about process and more fully understandable—to my colleagues and to my less enthusiastic students. Resistance, once again, had pointed me to where I needed to patch weak points in the fabric of my teaching. I set to work.

Spring semester, I created a pilot program with my 3-D printing project and a blogging approach I had used in the fall, got IRB clearance to conduct research, secured student permissions, and set to showing how my work was a suitable approach to teaching process, one that supported the work of the writing program, rather than detracting or distracting from it.

Then I got sick in February. “Flu-A plus bronchitis of unknown viral etiology.”

I had several international students in class whom I had just met in the last few weeks. They might have been sick and never known it. But testing being what it was then, my doctor said the state board of health did not consider me a candidate for Covid testing (at the time, one had to have traveled or had known contact with someone who was symptomatic, not anyone who had traveled), and so I did not get tested. By mid-March, when I was still sick and had inexplicably lost my sense of taste, my doctor decided that I likely had Covid, but since I could still not get tested, she asked me to quarantine. By this time, I was sleeping 14 hours a day, only coming to campus to teach, holding office hours primarily by Skype, and barely managing student response. It was the Wednesday before Spring Break and we were all waiting to be told we wouldn’t come back. We wouldn’t. I was relieved.

The listserv started blowing up with concerns in early March. Professors posting Chronicle of Higher Ed links and commenting on the dire future, discussions about how to handle the rest of the semester, worries about students and families, every possible post was added. I lurked and listened. We were instructed to do our best to put our courses online, and the faculty senate met to vote about regulating the semester as a hybrid semester (credit for hybrid and online courses has historically not been allowed at my school). I watched as the narrative began to unfold about who we were and what we were trying to do.

And then a beautiful thread came up about recruiting for the fall which included a concern that SLACs would not be able to “sell” what SLACs “do” if we were forced to stay online. One of my colleagues suggested that the life of the mind—his choice of words was apt—was what SLACs provide, and that this should be our focus.

I chanted the phrase “life of the mind” over and over for a while after reading that post. I thought about Eisenstein’s suggestion that this was a moment in which we could choose to make things into what we have always wanted them to be. I considered the next post in the thread, and wondered if we would create our dream academy.

Yuval Noah Harari, a professor of history at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, has a series of books about the history of humans, our future, and the lessons we can carry into the 21st century. Sapiens, Homo Deus, and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, all hinge on the basic premise that what differentiates homo sapiens from other animals is humans’ ability to create and believe in fictions. We create and believe in money, nations, marriage, culture, race, and many more. It is this ability to create and believe in what most academics will refer to as social constructs that allows us to cooperate flexibly in groups larger than 150 individuals—which is the limit of individuals who can cooperate in one-to-one relationships.

As we entered quarantine, I was reading Sapiens as well as the listserv. My class was mostly online. Our in-class meetings were for, as my colleague who did not allow note-taking put it, conversation. We discussed things together, went away to write about them and think about them, and came back to discuss our writing and our thinking and do it all again. So, as I watched the listserv, I thought I had nothing to worry about in my classes. We were set! I was good.

But resistance is my friend, and resistance decided to point out to me that I hadn’t thought much at all about what I was doing. My narrative, which I had formed and believed was that I knew how to teach online—I do. That I had experience teaching online—I do. And that I could handle this with no worries—here is where resistance found the weakness in the cloth. I might be able to handle a fully online class, having led several, but could my students.

On the listserv, concerns which I later kicked myself for not considering began to arise. What about students who didn’t have wifi at home? What about students who had to take care of younger siblings while at home because of parents’ work schedules? What about students who had to find alternative places to live because “home” as we might conceive of it for a college student was not an option? What about students who faced demands at home I could not even imagine? What if my students fell ill? The questions continued.

Resistance showed me what I had forgotten: every online course I had ever taught was taught to students who had signed up for an online course in an otherwise normal semester. I didn’t have this. I needed to quickly rethink this! But my students were digital natives! They would be fine, right?

Resistance, here, showed me once again that digital nativity means about the same as print nativity. Being born into a digital world and handed a screen at toddler-age is no more a guarantee of digital literacy than being born in a print world and handed baby books. One is as literate as one’s access, one’s practice, and one’s education.

At the start of the semester, I had asked my students to gauge their digital literacy on a 1-10 scale, and then define what that meant to them. My students considered themselves adequately to highly literate (most putting 6-9), and listed their ability to use their smart phones and Microsoft Word (and occasionally Excel) as their defining criteria. I was asking them to blog on a WordPress site that, while it was created for them, still required that they remember how to log in, how to tag posts, how to visit each other’s blogs, and how to respond to my blog, and more.

I reached, immediately, for empathy. When I had begun studying digital convergence, though I had been an early adopter (though I’m a Gen Xer, I have been working and playing with computers since I was a child), I struggled with some concepts. I struggled with new tech at times. I recalled my own resistance and learning to “play” with my tech, to break the rules, to try code that might snag and leave a machine hanging for hours. But my students needed a rewrite, and they needed it now.

And so, I let resistance point me to where I could strengthen the fabric. We had just begun the 3-D printing project, had just learned how to take photographs and some about photogrammetry. The writing assignment that was connected required on-campus research. I reached out to my students: Would we all be okay with changing this assignment completely? We would. And we did. Second, I changed the blogging assignment. Rather than ask students to write about their writing and printing processes each week, I asked them to write about their quarantine and Covid lives each week. One student began a weekly review of the best Netflix binge shows and new games to play for Covid. He had every student in his section commenting on his page. And finally, I asked us all to work in our small groups to be flexible about deadlines. Drafts had due dates so workshops and feedback could be provided, but students informed each other if they hit roadblocks, they used their LMS to talk about shifting a deadline by a day or two, and they learned to give each other grace. They taught me as well.

We got back to doing what, essentially, great courses in Liberal Arts classes do. We thought and read and wrote outside of class, and came together to have deep, meaningful discussions about them.

It was not the semester I had planned by any stretch. I had planned a research semester with outcomes and proof and publication. But the reality, while I will not argue that it has been in any way better than what I had envisioned, was nonetheless an important experience for me. I learned to lean into the resistance. To listen to it. I learned to ask, where are the weak points? What can be done better? How do others see this? And I learned to lurk productively. I believe that the spring semester in which none of us asked to be remote was a better training ground for me as an online teacher than my teaching online before had been. And from my summer session, fully online, student evaluations seem to suggest I may be on to something.

Covid is definitely not something to be wished for, and I am not a Pollyanna. But I believe crises can always be what we make of them. And in this crisis, I think we can make a case for the life of the mind—online.