Written by: Tyne Daile Sumner & Brian Martin (The University of Melbourne)

“Under observation, we act less free, which means we effectively are less free.”

- Edward Snowden“Let us have done with great systems embracing all the possible, and sometimes

even the impossible! Let us be content with the real …- Henri Bergson

In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff outlines the ‘psychic numbing’ that inures us to the realities of being ‘tracked, parsed, mined, and modified’ in the twenty-first century digital milieu (11). ‘Our dependency is at the heart of the commercial surveillance project,’ Zuboff writes of a situation we rationlise ‘in resigned cynicism’ or about which we ‘create excuses that operate like defense mechanisms’ (11). Zuboff’s pivotal term here, dependency, should remind us that even during moments of upheaval, the technologies we adopt to solve unexpected problems should never be accepted unconditionally, no matter how difficult or unprecedented the challenge at hand. For most Universities, the sudden shift to remote teaching in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated widespread uptake of Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs). Broadly theorized as places ‘where on-line distributed learning is facilitated’, VLEs are increasingly thought to be: ‘key elements in the education and training processes of students, since knowledge acquisition and technological skills are considered decisive factors in learning processes and future careers’ (Hiltz 85; Villamor 118). Yet while VLEs were already commonplace in tertiary institutions before the pandemic, the need to rapidly shift to online delivery has meant that many universities have adopted the virtual classroom under rushed conditions and without adequately addressing the problematic consequences of their associated surveillance tools and mechanisms.[1]

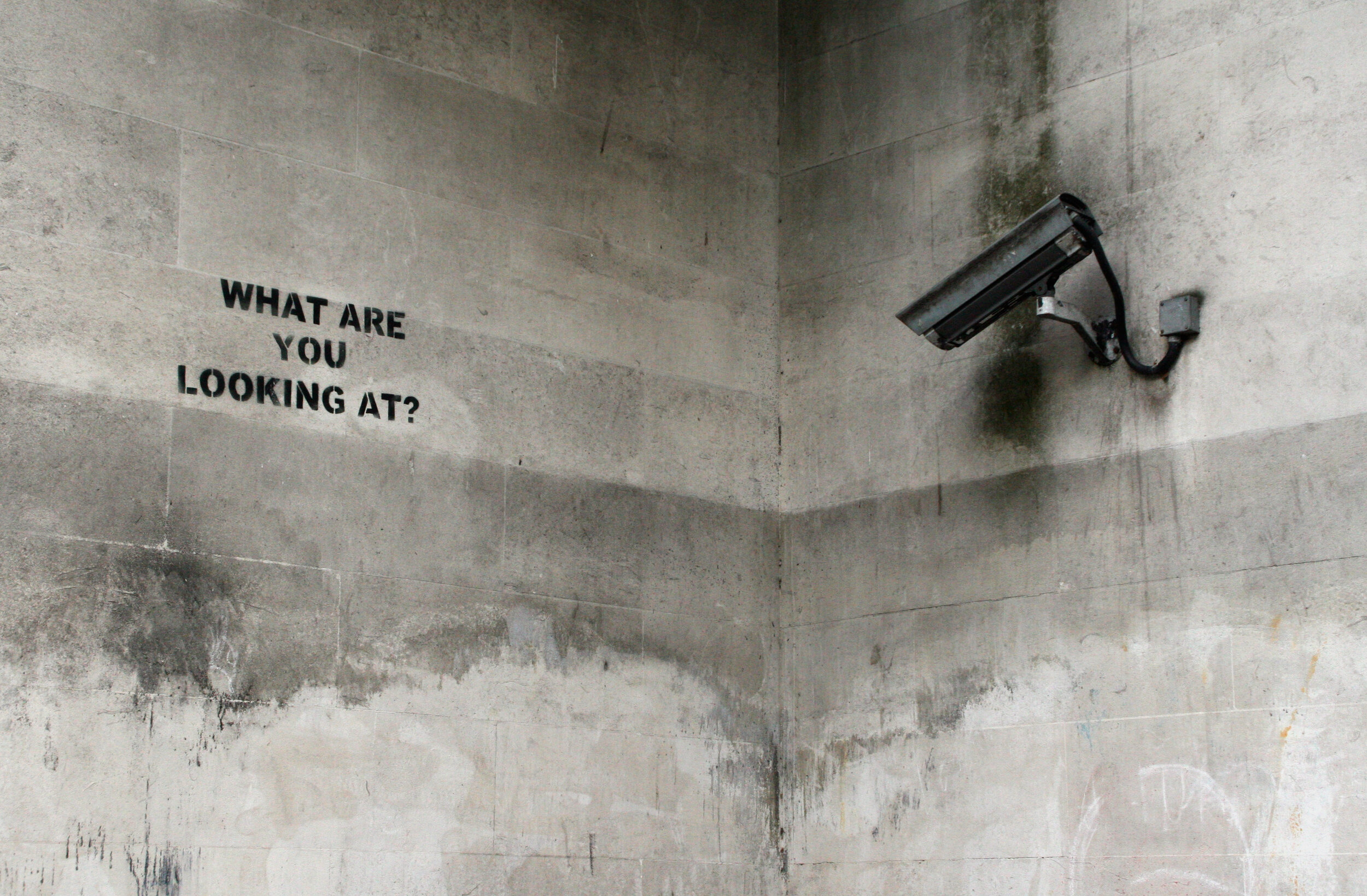

In this essay we contend that in urgent efforts to adopt new technologies for online education, students and teachers may be exposed to insidious forms of electronic surveillance that profoundly contradict the underlying intellectual and social aims of traditional pedagogy. To support this, we briefly examine scholarship at the intersection of education, digital technology and surveillance before moving to explore a range of issues of surveillance in VLEs. The discussion then considers potential modes of resisting surveillance, first from the perspective of students and then that of the teacher. Our conceptual framework is guided by questions of space, place and time in relation to VLEs, with a focus on the interwoven panoptical and synoptical gaze and its mediating power dynamics (Landhal).

'Visibility is a trap’: How did we get here and why does it matter?

Education scholars have previously argued that the use of new technologies in classrooms holds possibilities for the unwarranted surveillance of students and teachers. Boshier and Wilson, for example, examine several online courses to assess how ‘panoptic’ they were in comparison to face-to-face teaching. Compared to more traditional curriculum, they observed that in web-based courses the ‘intermittent participant’ has little to no flexibility. Noting a tendency among instructors to use online technology as the default, they describe how technology was used to ‘monitor every instance of participation or lack thereof,’ meaning that ‘instructor can keep a full textual record of a leaner’s contributions, while remaining invisible themselves’ (1).

Similarly, Warschauer and Lepeintre examine teacher-student relations on an international computer network to assess whether electronic computer networking in the classroom helps facilitate the ‘development of new teacher-student roles’, such as that theorised by Paolo Freire or whether it results in more effective coercion as described by Michel Foucault (67). While for Freire, new technology opens up a space for debate and discussion in which students and teachers ‘become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow,’ for Foucault, new technology extends and intensifies preexisting power dynamics, thus helping create a panoptic system of ‘surveillance and observation, security and knowledge, individualization and totalization, isolation and transparency’ (Warschauer and Lepeintre 249).

Following this logic, David Lyon’s oft cited sociological critique of surveillance in The Electronic Eye provides another useful framing for warnings about the digital panopticon. Lyon’s questions are as pertinent today as they were in the late twentieth century when he asks: ‘Are novel features appearing on the surveillance landscape that might alter the perception of change from challenge to threat?’ (162). While not focused specifically on the site of education, Lyon’s work nevertheless reveals the extent to which ‘electronic technologies facilitate the expansion of indirect, impersonal control of more knowledgeable organizations on which modern populations are increasingly dependent’ (162).

This relates to two important factors in the pedagogical dynamics of VLEs. First, the teacher is no longer required to be present with the student (in the same space and time) to enact surveillance. Second, Lyon’s assertion that behavioral norms are ultimately internalized by employees when in surveillant workplaces presents a logical corollary to the kinds of education being engaged in VLEs, where pathways through curriculum are codified and constantly monitored. If, for example, a student deviates (behaviorally, academically, socially) from the guidelines set out by the VLE, there are processes in place to correctively ‘nudge’ them back towards normative standards of engagement; standards which themselves are algorithmically engineered via comparisons across large cohorts to determine pathways that may not produce optimal learning outcomes (Knox).

More recently, Morgan Luck has highlighted some of the risks associated with universities establishing surveillance tools within VLEs. At the student level, he argues, the adoption of surveillance technologies ‘may result in students, especially the most gifted, feeling pressured to adopt practices that are not best suited to achieving their learning outcomes’ (1676). Luck notes that at the level of the teacher or manager, surveillance tools have the potential to ‘provide a means by which subject design could be further influenced by market forces’ (1676). This critique focuses on the problems that arise via the augmentation of the online resources folder (a unidirectional means of sharing information from the teacher to the students) with what he calls a ‘surveillance tool’, ‘a feature that can be attached to virtual classrooms to monitor how they are being used’ (1677).

'Everything is Designed’: Where are we heading and what can we do about it?

While many interventions are currently underway to facilitate the widespread demand for VLEs in response to the pandemic, two key instances present a significant challenge to what might be considered reasonable electronic surveillance. The first and most widespread of these is the replacement of timetabled physical classes with Zoom or similar video conferencing tools. The fixed layout of the Zoom gallery view, in which students are always displayed ‘front-on’ to not just the teacher but all peers, intensifies the power of the instructor’s gaze as a mediating dynamic. This scenario echoes the disciplinary function of the late nineteenth century ‘whole-class teaching’ model, in which students were required to sit at desks facing the teacher, who ‘from a raised seat offering ready survey of the pupils in their entirety, may easily command the attention and discipline of all’ (Richardson 110).[2] In this optical regime, the gaze of the teacher becomes once again a discrete disciplinary technology, reminiscent of Foucault’s well-rehearsed characterization of panopticism. However, the Zoom display also deviates somewhat from Foucault’s asymmetrical regime in which one part is made visible, another invisible, thereby rendering power tantamount to seeing without being seen.

In the confines of Zoom, not only are all students always on display in front of the teacher, the teacher is always on display in front the class. This formulation is consistent with Thomas Mathiesen’s theorisation of the synopticon: a place where the many see the few. Although this educational scenario may appear to constitute a rebalancing of power and, as Matheisen argues, is very much how power now operates under modern conditions, the opposite is indeed case. The duality of the Zoom gallery view – at once hypervisible, fixed and yet fragmented – works to generate a gaze in which students and teachers alike feel keenly aware of the need to perform such behaviors as attentiveness, enthusiasm and comprehension. Perhaps predictably, students have been found to resist this digitally mediated model by simply turning off their webcams, leaving teachers to engage with a blank screen.

A second development can be witnessed in efforts to measure and assess student participation and engagement via algorithmic means. Without physical attendance as a tangible measurement of participation, teachers are required to turn their attention to LMS functionalities such as contributions to discussion forums and emerging platforms and emerging platforms such as Perusall, which monitor engagement with reading materials. More general markers of engagement are also being used that seek to measure an overall impression of students’ interactions with learning resources and their peers and teachers via normative algorithms. Without critical and considered use, these systems have the potential to enact regulatory power through the written word in that ‘there is an emphasis on the textual artefacts to form an understanding of the author’s identity’ (Dawson 72). Hence, as Dawson observes

‘student contributions to a class discussion forum are examined and classified by both peers and teaching staff in order to form an associated identity and subsequent categorisation for future recognition’ (72).

Within these platforms, measures of quality of student experience become imbricated with measures of teaching performance, including metrics such as frequency of teacher presence, contributions to the LMS and timeliness of responses to student engagement. Additionally, predictive uses of data are becoming more common in institutional settings where intensive data-driven methods are being employed to better understand and anticipate undergraduate student bodies. In a recent article on the use of student data for predictive modelling, Whitman explores the ‘institutional shift from reliance on demographic data to what administrators, data scientists, and programmers’ at some universities have constructed as ‘behaviors’ (2). While demographic data has long been a tool used by universities to quantify and understand the student cohort, the move towards behavioral analytics in the classroom initiates a problematic turn in which, to borrow from Whitman, ‘students become data and their data possess more veracity than the students themselves’ (9). As a result, the discursive separation of ‘attributes’ from ‘behaviours’ allows for scenarios in which student behaviours become actionable outputs of a data-driven forms of institutional management and surveillance.

‘Mechanization Best Serves Mediocrity’: The Panoptic Classroom and Students

It is now becoming clear that within VLEs students encounter modes of spatial and temporal surveillance that work to normalise the mediation of their learning processes, academic progression and social engagement. To understand how resistance to surveillance in VLEs might be possible, it is important to first recognise that virtual spaces are analogues of the real world in the way that humans interact with them. Thus, the use of visual, auditory and data-driven monitoring in VLEs should be seen as equivalent to, or in most instances, amplified versions of how these the processes might be experienced in person. Tyner provides a useful lens for thinking about the effects of surveillance in VLEs in his examination of the implications of space, resistance and discipline in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Detailing the ‘spatial and temporal control of everyday activities’ that serves to regulate spaces within a totalitarian society,’ he suggests that Orwell’s novel illustrates how ‘the production of knowledge through the act of writing may forge spaces of resistance within disciplined spaces’ (129).

In the highly mediated, monitored and assessed confines of the VLE students may, like Orwell’s protagonist Winston, feel vulnerable to attacks on their individuality and sense of identity. By virtue of participating in VLEs, students are subjected to the disciplining of space and time, akin to the ways in which walking home or spending time alone are overseen by Orwell’s omniscient Big Brother. Winston’s experiences of surveillance in the novel are thus analogous to those encountered in the VLE, where tightly scripted instructional design prevents students moving through the space and time of the classroom by any means other than those prescribed. Actions must proceed in a pre-determined order, not before the allotted time and in accordance with a matrix of online quizzes and modules; all affronts to students’ autonomy to self-direct and self-regulate their learning (Dawson; Luck).

In the dystopian world of Orwellian surveillance, Winston’s subjectification is achieved by the disciplining of body language and facial expressions via the telescreen. Meanwhile in the contemporary VLE, Orwell’s fictional maneuvers become reality as students interact with ‘bots’ capable of not only monitoring but interpreting, responding to and potentially disciplining emotion. VLE capabilities such as Cadmus, which monitors students’ writing processes via constant observation, could therefore potentially be considered analogous to the policing of students’ thinking. The manipulation of students’ thinking, actions and behaviour under surveillance in VLEs in turn influences the content and compositional structure of their contributions to discussion forums in that they are told precisely what is expected of them and therefore positioned to align their written comments with those already visible (Dawson).

These issues are further amplified by the VLE ‘performance dashboard’, where students can compare their academic progress through either compulsory or voluntary modules and discussion questions with that of other students, resulting in the showcasing of apparent normative progression through the course or subject. These dashboards and the data that underpin them extend discipline into the future by triggering interventions designed to ensure students stay on track with the ‘standard’ distribution of the cohort, resulting in ‘an almost total loss of human agency’ (Knox 13). These effects on the autonomy of students should prompt us to question what the phenomenology of being a student in the post-COVID milieu might risk becoming. As students begin to understand the intricacies of the ways that they are being overtly and covertly positioned and ‘nudged’ by classroom surveillance as well as the normalising algorithms at work in predicting their decisions, will they begin to modify their behaviour to appease the expectations of the codified ‘teacher’ in the VLE or will they resist, (through whatever means possible) direct attacks on their agency and self-regulation?

‘The Art of Orientation’: The Panoptic Classroom and Teachers

By virtue of their professionalism and praxis, teachers embody the purpose of education, an objective greater than measured performance against normative learning outcomes (Biesta). Scholars interested in the idea of education as form of moral care have also observed this crucial disjunction, arguing that by using their empathy and judgement, teachers should design experiences for students that deeply consider their experience of being the world: where they have come from, who they are now, and what they imagine their future self will become (Gregory). This represents an ethical and balanced approach to education, one that inherently resists surveillant disciplining and the regulation of identities via deterministic algorithms that prioritize ‘obedience’ over ‘learning’ (Morris & Stommel; Loc 798). Quay positions the role of the teacher as one that provides students the freedom to learn – a delicate balancing act also described by Heidegger as leaping ahead of the student, rather than leaping in, as algorithms are designed to do. These educational philosophies prioritise ways of being and experiences of doing that view education as a threefold undertaking: qualification, socialisation, and subjectification. In the unregulated turn to VLEs, this tripartite goal is under threat as the electronic panopticon works to generate the ‘learnification of education’ (Biesta 76). Ultimately, excessive focus on measuring and attaining learning outcomes for the purpose of qualification skews the balance between these three interconnected purposes of education and diminishes the role of the teacher in making judgements about how they should be priorisited for different pedagogical purposes and at different times for individual students.

As Universities increase their investment in online infrastructure to enhance VLEs, teachers may be tempted to depend upon the convenience of digitally-measured, ‘clickable’, proxies for learning and student engagement. Moreover, as teaching loads increase in response to the fiscal and administrative upheavals of the pandemic, it may be seductive to rely upon normative dashboards and predictive analytics for ‘nudges’ that guide students towards specific predetermined learning outcomes (Knox). However, unchecked use of electronic augmentations to teaching and learning has the potential to result in unconscious reliance and the eventual embeddedness of these technologies in teaching practice thereafter. The more teachers depend upon them, the more difficult it may become to detox the contemporary curriculum from the seemingly benign but ultimately damaging effects of surveillant technologies. To avoid this, teachers may benefit from a resistant praxis that returns ‘teaching back to education’ (Biesta 35). A first step in this process might involve increasing literacy among teachers of the sociological impacts of educational surveillance and algorithmically deterministic VLEs. Second, teachers might consider more closely the advantages of experiential and practice-based outcomes for students as a means of pragmatically decoupling curriculums from electronic mediation. Third, teachers might work to more proactively and transparently orient students to the virtual classroom space they find themselves inhabiting and consequently the power dynamics to which they are exposed so as to encourage critical agency in resisting otherwise invisible surveillant aspects of this domain.

Finally, for teachers to avoid becoming the targets of student-led resistance in this intensifying surveillant turn, they will likely need to construct learning activities and assessment that facilitate opportunities for students to inhabit surveillance-free virtual and physical spaces; a practice that could effectively restore lost trust between student and teacher (Knox; Stommel). Specifically identifying the utility of space and ‘place’ as heuristics for increasing student collaboration and belonging among communities of peers affords opportunities for autonomous learning, free from surveillant and temporal discipline. In this way, the ontologies of care proposed by Dewey deserve consideration as a reminder to resist our dependency to adopt deterministic disciplined educative experiences that are limited by uncertain predictions about an unknowable future – something Dewey himself considered a betrayal of students under our care. In doing so we will be inspired to create spaces, experiences and aesthetics for different ways of being that may provide respite from the unrelenting occupation of being a student under surveillance and provide balance to the broader purpose of education.

Resisting Change, Changing Resistance: Final Thoughts and Clarifications

With the current upheaval of COVID-19 still unfolding across the University sector, our aim in this essay has not been to propose material solutions or recommendations to what is a rapidly evolving situation. Rather, we have set out to provide a series of framing questions and considerations that will hopefully offer productive approaches moving forward. Some of the key questions we have set out to provoke include: How is both an explicit and implicit awareness of surveillant mechanisms affecting student engagement in the context of a widespread move to online teaching and learning? What strategies are available for students and teachers alike to resist electronic surveillance in the classroom? What does the current situation mean for teachers’ capacity to exercise professional judgement and care as they adapt and respond to new pedagogies delivered in VLEs? And finally, how are educators currently able to understand or assess the extent to which they might be complicit in the growth of problematic commercial platforms? To borrow from David Lyon in bringing these provocations together: ‘What sorts of resistance are placed in the path of the machine, for what reasons and with what effects?’ (161). As we have argued, the aesthetics and experience of being a student have undertaken a seismic shift in the urgent uptake of VLEs, risking a loss of self-regulation and self-determination through the intensification of panoptic and synoptic gazes and normalising algorithmic discipline. In light of these and other considerations, the crisis could have a silver lining in that teachers, as the guardians and embodiment of education, may experience a renaissance in their agency to critically assess and make judgements about the digital tools, techniques, platforms and facilities at their disposal. Moreover, as students become increasingly aware of their subjectification within VLEs they may begin, as Foucault suggests, to refuse what they are becoming.

References:

Biesta, G. (2015). What is education for? On good education, teacher judgement, and educational professionalism. European Journal of Education, 50(1), 75-87.

Boshier, R., & Wilson, M. (1998). Panoptic variations: surveillance and discipline in web courses. In: Proceedings of the Adult Education Research Conference. University of British Columbia, Vancouver (at http://www.edst.educ.ubc.ca/aerc/1998/98boshier.html accessed 17/04/2002)

Dawson, S. P. (2006). The impact of institutional surveillance technologies on student behaviour. Surveillance & Society, 4(1/2), 69-84.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Collier Books (LW 13.2–63).

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

Gregory, M. (2000). Care as a goal of democratic education. Journal of moral education, 29(4), 445-461.

Hiltz, S. R. (1994). The Virtual Classroom: Learning Without Limits Via Computer Network. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Knox, D. (2010). A good horse runs at the shadow of the whip: Surveillance and organizational trust in online learning environments. The Canadian Journal of Media Studies, 7, 07-01.

Landahl, J. (2013). The eye of power (-lessness): On the emergence of the panoptical and synoptical classroom. History of Education, 42(6), 803-821.

Luck, M. (2010). ‘Surveillance in the virtual classroom.’ In Interaction in Communication Technologies and Virtual Learning Environments: Human Factors. p. 160-169.

Lyon, D. (1993). ‘An electronic panopticon?’ A sociological critique of surveillance theory.’ Sociological Review, 41: 653-678.

Mathiesen, T. (1997). The viewer society: Michel Foucault's ‘Panopticon' revisited. Theoretical Criminology, 1(2), 215-234.

Morris, S. M., & Stommel, J. (2018). An urgency of teachers: The work of critical digital pedagogy. Hybrid Pedagogy Inc. Retrieved from: amazon.com.au

Orwell, G. (2008). Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Novel. London: Penguin.

Quay, J. (2013). Education, experience and existence: Engaging Dewey, Peirce and Heidegger. Routledge.

Richardson, G. (1998). Rudenschöld. Samhällskritiker och skolreformator. Stockholm: Carlssons.

Trezise, K., Ryan, T., de Barba, P., & Kennedy, G. (2019). Detecting Academic Misconduct Using Learning Analytics. Journal of Learning Analytics, 6(3), 90-104

Tyner, J. A. (2004). Self and space, resistance and discipline: a Foucauldian reading of George Orwell's 1984. Social & Cultural Geography, 5(1), 129-149.

Villamor, J. (2008). The Subject Computer Experience of University Students. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 5, 118-128.

Warschauer, M., & Lepeintre, S. (1997). Freire’s Dream or Foucault’s Nightmare: Teacher–Student Relations on an International Computer Network. In: Debski R, Gassin J, Smith M (eds). Language Learning Through Social Computing. Applied Linguistics Association of Australia, Parkville, Australia

Whitman, M. (2020). “We called that a behavior”: The making of institutional data. Big Data & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720932200

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: Public Affairs.

Footnotes

[1] Examples of software platforms upon which VLEs have been established include Blackboard, Canvas, Brightspace, Moodle and Sakai©.

[2] On the shift from monitorial teaching towards whole-class teaching, see Agneta Linné, ‘The Lesson as a Pedagogic Text: A Case Study of Lesson Designs’, Journal of Curriculum (2001): 129–56.